MHQ data highlights the profound relationship between sleep and exercise and mental wellbeing and the degree of sleep deprivation and sedentary lifestyle of he world.

Research into mental health disorders has regularly highlighted the importance of social and environmental factors in the onset and trajectory of symptoms. Often the focus is on a person’s life experience, in particular their experience of life trauma or adversity. But there are many other ways in which a person’s life situation can impact their mental health. Two factors which are often highlighted as contributing to the trajectory, and potentially also in the self-management of mental health difficulties, are sleep and exercise.

See related post The Impact of Life Experience on the Human Brain

The role of sleep in mental health.

The importance of sleep is undisputed and over the past few decades there have been a wealth of studies which have tried to explain why sleep is so important not just to the body, but also to the brain. On top of this, there are also many studies demonstrating the severe consequences of poor sleep quality, or sleep deprivation, on both mental and physical health. This includes having poorer cognitive performance [1-4], increased stress reactivity [5] and results in a series of neurobiological changes at the level of the brain [6]. One question that research has attempted to answer is whether not getting enough sleep, or poor sleep quality, is a trigger or a consequence of poor mental and cognitive health, or, more likely, a vicious cycle of both. For disorders like depression, there have been several longitudinal studies which have addressed this and concluded that as well being a symptom, sleep complaints often precede the onset of depression [7]. For other psychiatric disorders sleep difficulties have also been reported [8] but the relationship isn’t always straightforward. For example, research into ADHD reveals a complex picture of interactions between sleep difficulties and other symptoms, compounded by the psychostimulant treatments that are often prescribed [9].

How does exercise benefit mental health?

Similarly, there are hundreds, if not thousands of studies investigating the impact of exercise on mental health. So much so, that when you look at those examining the benefits of exercise on depression, there are not just meta-analyses of these studies, there are systematic reviews of these meta-analyses [10-12]. Although the benefit of exercise to mental health is hard to deny given the vast number of supportive studies, what’s less clear is the magnitude of the benefit and how this varies across type of exercise, individuals and symptom profiles.

Measuring sleep in the MHQ

Within the Mental Health Million Project, we can examine the relationship between mental wellbeing, as measured by the MHQ, and the degree to which respondents are getting enough sleep, as well as how regularly they are exercising.

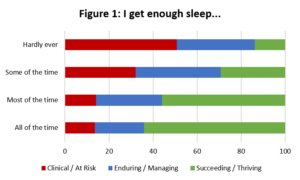

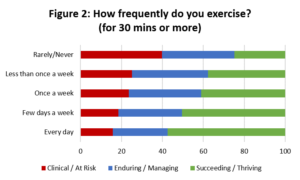

When we look at the MHQ score profiles across the ~20,000 respondents who have completed the MHQ so far, we find a dramatic relationship emerging. A full 50% of those who hardly ever got enough sleep have or are at risk for clinical disorders. Contrast that to only 14% of those who get enough sleep all the time. In other words people who never get enough sleep are almost 4X as likely to have mental health issues. That should be enough to send everyone to bed on time.

Yet only 12% get enough sleep all of the time and almost half the world (at least the world of MHQ respondents) is seriously sleep deprived.

Measuring Exercise in the MHQ

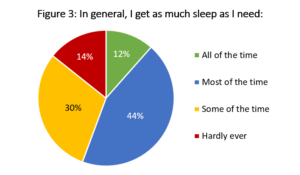

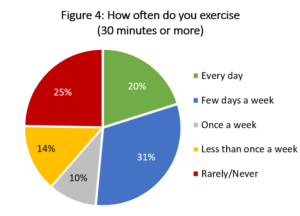

Similarly, when we take a look at the frequency of exercise, 40% of those who report that they rarely or never exercise had or were at risk for clinical mental health disorders. In contrast only 18% of those who exercised 30 mins or more everyday were at risk for a clinical disorder. In other words non-exercisers are twice as likely to have a mental health disorder.

Yet half the world (of MHQ respondents) are not regular exercisers and a full quarter rarely or never exercise.

With this kind of profound difference it’s entirely possible that mandating everyone to the gym and then straight to bed could have an enormous impact on the burden of mental health. Yet more insights are needed into the direction of cause and effect, the nature of symptoms associated with poor sleep and exercise and differences by age and gender. For example, when you look at sleep problems across the 55-64 age group, then the proportion of females who rarely get enough sleep increases to 20%, compared to 13% for males, and corresponding to known sleep problems during menopause[1]. In contrast, this gender difference was not observed in the 18-24 age range.

Using the MHQ and the Mental Health Million Data in your Research.

These are just a few examples of how data from the MHQ is allowing us to explore mental health and wellbeing profiles of individuals and populations across the globe. To find out more about how you can access the data being produced using the MHQ to probe these relationships further, please fill in our data access request form that can be found here. If you are a researcher interested in the relationship between sleep or exercise and mental health, then the MHQ also offers an assessment framework that you can add to and tailor to the needs of your research studies, adding in additional questions that allow you to delve more deeply into the nuances of these relationships, whilst offering standardization and a transdiagnostic perspective to psychopathology that isn’t possible with any other assessment tools. You can find out more about the MHQ in our recent JMIR paper here. If you want to use the MHQ in your research then please see here.

References:

[1] Lowe, C., Safati, A., & Hall, P. (2017). The neurocognitive consequences of sleep restriction: A meta-analytic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 80, 586-604. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.010

[2] Tarokh, L., Saletin, J., & Carskadon, M. (2016). Sleep in adolescence: Physiology, cognition and mental health. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 182-188. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.008

[3] Dzierzewski, J., Dautovich, N., & Ravyts, S. (2018). Sleep and Cognition in Older Adults. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 13(1), 93-106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.09.009

[4] McCoy, J., & Strecker, R. (2011). The cognitive cost of sleep lost. Neurobiology Of Learning And Memory, 96(4), 564-582. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.07.004

[5] Meerlo, P., Sgoifo, A., & Suchecki, D. (2008). Restricted and disrupted sleep: Effects on autonomic function, neuroendocrine stress systems and stress responsivity. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 12(3), 197-210. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.007

[6] Krause, A., Simon, E., Mander, B., Greer, S., Saletin, J., Goldstein-Piekarski, A., & Walker, M. (2017). The sleep-deprived human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(7), 404-418. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.55

[7] Meerlo, P., Havekes, R., & Steiger, A. (2015). Chronically Restricted or Disrupted Sleep as a Causal Factor in the Development of Depression. Sleep, Neuronal Plasticity And Brain Function, 459-481. doi: 10.1007/7854_2015_367

[8] Krystal, A. (2012). Psychiatric Disorders and Sleep. Neurologic Clinics, 30(4), 1389-1413. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.018

[9] Hvolby, A. (2014). Associations of sleep disturbance with ADHD: implications for treatment. ADHD Attention Deficit And Hyperactivity Disorders, 7(1), 1-18. doi: 10.1007/s12402-014-0151-0

[10] Hu, M., Turner, D., Generaal, E., Bos, D., Ikram, M., & Ikram, M. et al. (2020). Exercise interventions for the prevention of depression: a systematic review of meta-analyses. BMC Public Health, 20(1). doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09323-y

[11] Di Lorito, C., Long, A., Byrne, A., Harwood, R., Gladman, J., & Schneider, S. et al. (2020). Exercise interventions for older adults: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Journal Of Sport And Health Science. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.06.003

[12] Wegner, M., Amatriain-Fernández, S., Kaulitzky, A., Murillo-Rodriguez, E., Machado, S., & Budde, H. (2020). Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses: Exercise Effects on Depression in Children and Adolescents. Frontiers In Psychiatry, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00081

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5810528/