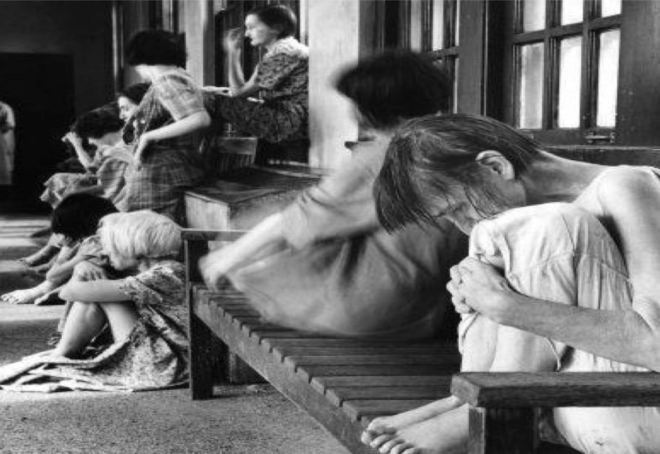

The way society handles the deviant variants and dispositions of the mind has a brutal history with some remarkable and exceptional examples that can teach us all something about the better sides of human nature.

In 1818 a man was confined to the Hospital of Bethlem, the oldest psychiatric facility in Europe – in those days known as lunatic asylums. He was described as a ferocious maniac who evinced a character of desperation and vengeance more characteristic of a tiger than a human being and was deprived of rational faculties, routinely venting blasphemous imprecations, and abuse against his fellow patients calling them ‘stinking Lloyd’, ‘Rascally Jack Hallwood’, ‘Thieving old Coates’ and ‘Lousy Jenkins’. Like many, he spent much of his days in restraints. Indeed, many spent their days chained to the wall in filth and cold until death.

In this very same hospital – it is reported that they made an income of as much as 400 pounds a year displaying inmates to the public and goading them into a frenzy for the ‘amusement of the sightseers’.

However, already a movement for change had been in the making led in part by French physician Philippe Pinel. Driven by a sudden turn in the mental state of a friend that led to suicide he spent many years observing the mentally afflicted. He is in large part credited with the decriminalization of mental health advocating that its afflicted should be managed by careful observation and moral treatment. This ‘moral treatment’ is considered the earliest form of psychotherapy.

see related post The Challenges of Mental Health Diagnosis

Lunatic Asylums

Pinel dies in 1826 but his message had begun to spread across Europe. In 1852 the first volume of the Lancet advertised a monograph called Notes on Lunatic Asylums in Germany and other parts of Europe by W.F. Cummings which could be purchased for one shilling. By this time much progress has been made. He says:

Of all the ameliorations in the condition of the human race which the present century has witnessed, there is none on which the mind of the philanthropist will more complacently dwell than on the great advance which has been made in the knowledge and treatment of mental disease. Until the close of the century the unfortunate beings “Stricken of God” were considered as outcasts of the human family, their misfortunes treated as a crime; and the individual in whom insanity had declared itself no longer worthy of the privileges of man.

Cummings undertook a tour of ‘lunatic asylums’ and ‘Institutes for Education of Idiots’ to bring to public awareness the best practices of such moral treatment and call out those who still follow the antiquated practices of restraints and torture. In it he describes attempts of various methodologies from committing the patients to different types of labor that ‘distract’ from their affliction to compassionate methods of teaching. He also describes the 50 to 90% that he claims experience remarkable turnarounds and even cures.

On this count the United States perhaps lagged behind and it is easy to find many descriptions of harsh mistreatment well into the 1900s. It was not till the end of the 1800s that American neurologists such as Weir Mitchell and Bernard Sachs noted a dissociation of management of lunatic asylums from science and sought to bring together neurologists with the ‘Superintendents of Lunatics’ to move towards patient care rather than simply management.

The Village of Gheel

In our societal narrative on how we deal with variants and disorders of the mind the Village of Gheel stands out as a unique experiment in Belgium, that persists even today. The Village of Gheel is about 35 miles from Antwerp and unremarkable in view but perhaps unique in every other way. In 1852 when Cummings visited it had a population of 10,000 that included 1,000 ‘lunatics’ who had been sent there for care. Yet the ‘lunatics’ did not live in an asylum but were taken in by the villagers as boarders in their homes for a small sum of 200 pounds a year. Each home often harbored two to three, living free and helping with the chores. This culture has its origins in a story from the sixth century when an Irish princess call Dympna fled from her father’s violent incest to the village of Gheel where he followed her and severed her head. Two ‘lunatics’ witnessed the act and were immediately jolted to reason. Posthumously Dympna was declared the saint and patron of lunatics and a church erected in her name. The insane began to come from all over, participating in a procession for 9 days around the church before they were taken in by the village residents.

Remarkably the tradition of taking the mentally ill into their homes and family persists even today and may tell us much about the human mind and the way we embrace its many manifestations. Watch it in this video: