There are learning and memory differences between those with PTSD but is it that PTSD causes those deficits or the other way around?

It was only in the 1980s, that the American Psychiatric Association added Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to the third edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). Until then, terms such as shell shock, soldier’s heart, combat fatigue or war neurosis was used to describe what is today known as PTSD. PTSD is a anxiety disorder that occurs when someone witnesses or experiences a traumatic event and involves the following symptom clusters [1]

1) Intrusive memories that may include nightmares and flashbacks,

2) Avoidance of people and activities

3) Emotional numbness and

4) Hyper-arousal symptoms ( for e.g. bursts of anger, increased startle to unexpected noises ).

Effect of PTSD on working and declarative memory

Several studies have reported disturbances in memory processing of PTSD patients. The hippocampus, amygdala, prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices have been mainly implicated in memory processing. As a consequence, most neuroimaging studies have focused these brain regions in search of aspects associated with memory processing. Here are some of the findings.

MRI

Using structural MRI, smaller hippocampal volumes have been reported in patients with PTSD [2-4], which could be due to elevated levels of corticosteroids that can cause neurotoxicity in the hippocampus. However, whether the volumetric difference is due to the trauma or if it is a pre-existing trait that predisposes people to stress is poorly understood. Furthermore, whether smaller hippocampal volume in PTSD contributes to deficit in declarative memory also has contrasting views, with several studies showing no significant correlation between hippocampal volume loss and declarative memory [5-6]. Roles of other brain regions such as the frontal cortex have also been investigated and reduction in their volumes using structural MRI as well as reduced activation during an encoding and retrieval of 12 word-pair associates learning tasks [7]. Interestingly, with the pediatric population, more consistent results have been found with regard to reduction in the volume of frontal cortex than in hippocampus in the PTSD group compared to the non-PTSD group, suggesting a stronger role of PTSD in deficits related to acquisition and learning processes that are regulated by the prefrontal cortex, than the problem with retention in which the hippocampus is more heavily involved.

EEG and MEG

Results from a dual task study (Sternberg memory task and arrow flanker) using electroencephalography (EEG) [8] demonstrated that the PTSD subjects were less accurate than the controls (see Figure 1), which was also in agreement with behavioral analysis from the same study. The major finding using EEG was that the PTSD patients did not show any differences between ERPs to the probe that was part of the previous memory set (old) or was not part of the memory set (new), in the dual-task condition. However, patients with PTSD were able to perform a single-task (working memory task) in isolation, showing no significant difference from controls. It is only during the maintenance period (which had a distracting task – arrow flanker task), the PTSD patients declined significantly in accuracy and the associated ERPs no longer differentiated old and new probes.

Figure 1 : For both the groups in the single-task condition (Sternberg memory task), beginning at 300 ms, positive shift for the old probes that are correctly recognized, relative to new probes that are correctly rejected was observed. However the dual-task condition (Sternberg memory task and arrow flanker), this was observed only for the controls [8].

Magnetoencephalography (MEG), has also been used to examine working memory deficits in PTSD. In one of the first few studies utilizing MEG, Mcdermott et al. showed that veterans with PTSD exhibited abnormal oscillatory activity during working memory, encoding and maintenance task [9]. In particular, they observed α desynchronizations in controls in left supramarginal and inferior frontal gyrus, while in the case of PTSD veterans, right hemispheric homologue areas were also additionally recruited to aid in task performance. Furthermore, their results also showed that these brain regions were temporally engaged in parallel.

Figure 2: Group differences using beamformer between controls and PTSD veterans during encoding (blue), transition (white) and maintenance (Red) phase in 9–12 Hz α activity in the right hemisphere (right inferior temporal gyrus) [9]

Does PTSD cause memory deficits or the other way around?

In summary, studies from neuroimaging have shown that patients with PTSD exhibit impaired working memory capacity relative to controls. Does that mean memory deficit is a consequence of PTSD? The studies have relatively small sample sizes relative to the overall population and do not account for all of the natural variation among individuals. In addition, the effect sizes are small.

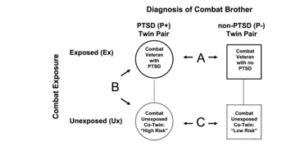

There is also the possibility that it is the other way around – that preexisting learning and memory deficits contribute to the likelihood of developing PTSD. A study found that the combat-unexposed co-twins of PTSD combat veterans (See Figure 3) performed similarly in tasks related to intellectual performance, memory and attention, as their brothers and it was significantly lower than that of the non-PTSD population of combat veterans (and their brothers) [10].

Figure 3: The figure represents four participant groups – Twin pair – Combat xxposed with PTSD (ExP+), Combat unexposed (UxP-) and the non-PTSD twin pair defined analogously [10].

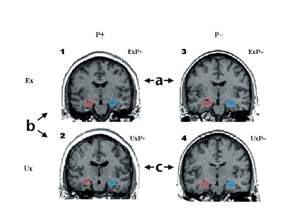

The same group also showed that monozygotic (identical) twin pairs that had severe PTSD, which included both exposed (ExP+) and unexposed (UxP+) members, had a significantly lower hippocampal volume than the non-PTSD (ExP-, UxP-) twin population [11]. More importantly, the unexposed PTSD members had comparable hippocampal volume to their exposed PTSD twins, but significantly smaller volume compared to both exposed and unexposed non-PTSD group.

Since these were identical twins, and there was no significant difference in the hippocampal volume of exposed and unexposed PTSD twins or in the cognitive performance, the results from these studies indeed suggest greater influence imposed by familial vulnerability in the development of PTSD, than any exposure to neurotoxicity inducing environments.

Figure 4 : (a) Contrast between hippocampal volumes of combat exposed PTSD and non-PTSD groups. (b) contrasts between combat exposed and unexposed, PTSD twins and (c) contrasts between combat unexposed PTSD and non-PTSD groups [11].

References

1. Honzel, N., Justus, T., & Swick, D. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with limited executive resources in a working memory task. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral

2. Bremmer, D., Randall, P., Scott, T., & Bronen, R. (1995). MRI-Based Measurement of Hippocampal Volume in Patients With Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 973–981.

3. Bremmer, J., Randall, P., & Vermetten, E. (1997). Magnetic resonance imag- ing-based measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress dis- order related to childhood physical and sexual abuse–a preliminary report. Biol Psychiatry, 41, 23–32.

4. Stein, M. B., Koverola, C., Hanna, C., Torchia, M. G., & McClarty, B. (1997). Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse. Psychological medicine, 27(4), 951-959.

5. Woodward, S., Kaloupek, D., & Grande, L. (2009). Hippocampal volume and declarative memory function in combat-related PTSD. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 15, 830–839.

6. Nakano, T., Wenner, M., & Inagaki, M. (2002). Relationship between distress- ing cancer-related recollections and hippocampal volume in cancer survivors. Am J Psychiatry, 159, 2087–2093.

7. Kitayama, N., Vaccarino, V., Kutner, M., Weiss, P., & Bremner, J. D. (2005). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurement of hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: A metaanalysis

8. Honzel, N., Justus, T., & Swick, D. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder is associated with limited executive resources in a working memory task. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14(2), 792–804. http://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-013-0219-x

9. Mcdermott, T. J., Badura-brack, A. S., Becker, K. M., Ryan, T. J., Bar-haim, Y., Pine, D. S., … Wilson, T. W. (2016). Attention training improves aberrant neural dynamics during working memory processing in veterans with PTSD. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. http://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-016-0459-7

10. Gilbertson, M., Paulus, L., & Williston, S. (2006). Neurocognitive function in monozygotic twins discordant for combat exposure: Relationship to post- traumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol, 11, 484–495.

11. Gilbertson, M., Shenton, M., & Ciszewski, A. (2002). Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci, 5, 1242–1247.