Frontal asymmetry has been touted as a marker for depression but the results are stacking up against it. Some metanalysis suggests that rather than being a marker for symptoms it may reflect differences in gender and treatment.

Frontal asymmetry is a widely tested EEG biomarker in clinical research. Over the past few decades it has been most widely applied to depressive disorders in an attempt to find a more objective way to predict treatment response, or even aid diagnosis (see The Frustration of Treating Depression and The Difficulty of Diagnosing Depression). However, despite the large body of research conducted to date, there is still significant uncertainty as to its validity as a potential clinical marker (see here for a recent review). What’s more, frontal asymmetry isn’t unique to depression and has also been observed in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, ADHD, anxiety, OCD and PTSD leading to the suggestion that it is the symptoms, not the diagnosis, which is more important.

What is Frontal Asymmetry?

Frontal asymmetry is typically calculated in the alpha band (adults ~8-12Hz; infants ~6–9 Hz), although asymmetry is sometimes measured across other regions, (e.g. parietal sites), and in other bands (e.g. beta). It’s algorithm is commonly defined as the natural log of the ratio of the alpha band on the right and left side (ln(right alpha/left alpha) or ln(right alpha] − ln(left alpha)), often computed across mid-frontal (e.g. F4-F3) and lateral frontal (e.g. F6-F5, F8- F7) sites. It can be analyzed when the participant is at rest (trait asymmetry), or during a specific task (state asymmetry).

Frontal asymmetry metrics are based on the assumption that there is a broadly inverse relationship between alpha activity and cortical activity, due to its suppressive nature (see Alpha Oscillations and Attention). They are also motivated from proposed differential roles of right vs left frontal regions. For example, motivational theories suggest that increased left sided cortical activity (as shown by reduced left alpha activity and more positive frontal asymmetry scores based on the above calculation) is associated with approach behaviors, whilst increased right sided cortical activity is associated with withdrawal tendencies. Other theories suggest an affective nature of the asymmetry (left= positive affect; right = negative affect), whilst other theories are based on the individual’s capacity to regulate their emotional response to a situation (e.g. the moderator-mediator theory). None of these theories, however, are thus far proven.

Frontal Asymmetry and Depression

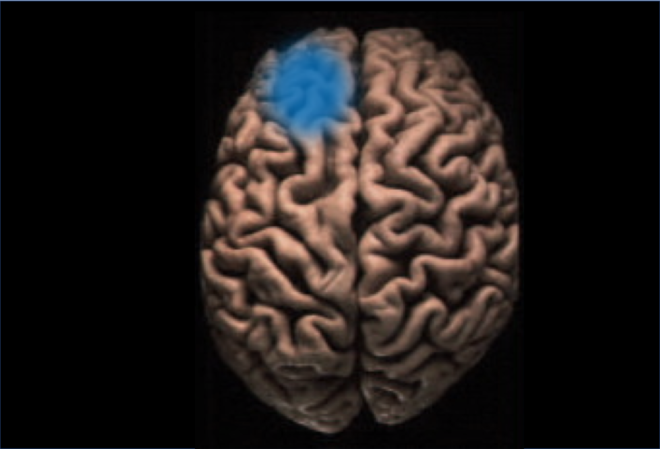

In the context of depression the hypothesis arising from these theories is that patients with major depression may have a tendency to show greater right sided cortical activity and/or reduced left sided activity (i.e. lower frontal asymmetry scores), or show a significant correlation between asymmetry scores and questionnaire ratings. However, across the large number of studies conducted to date, the literature remains unclear. For example, a meta-analysis conducted in 2006 from Syracuse University with 33 studies (n=2761) found evidence in favor of frontal asymmetry being a marker for depression with the highest r value reported by any one study at 0.6 but an average r value across studies of only 0.29. In contrast, a more recent meta-analysis from the Netherlands in 2017 with 16 studies (n=4044), as well as systematic review of 44 studies also in 2017, concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the use of frontal asymmetry as a biomarker for depression (see EEG Based Biomarkers and the Many Pitfalls). In addition, one of the largest single EEG studies (1008 patients, 336 controls) conducted in 2016 also failed to find any conclusive link across symptoms in the depressed group, but instead found that frontal asymmetry more strongly reflected gender (see figure) and treatments.

From Arns et al 2016. Differences in eyes closed alpha CSD between MDD participants and controls assessed using eLORETA. This figure further visualizes the effects of lower posterior cingulate and higher rACC alpha in MDD participants. (B) Male and female data shown together. (C) Female-only data. (D) Male-only data.

From Arns et al 2016. Differences in eyes closed alpha CSD between MDD participants and controls assessed using eLORETA. This figure further visualizes the effects of lower posterior cingulate and higher rACC alpha in MDD participants. (B) Male and female data shown together. (C) Female-only data. (D) Male-only data.

Methodological Concerns

One of the major concerns highlighted in these meta-analyses is the significant variability in methodologies. These include the choice of EEG parameter (e.g. referencing and recording length are thought to make a difference), and the clinical populations studied (e.g. age, gender and depression severity or subtype) (see here for a discussion). In addition, comorbidities, especially between depression and anxiety add further confounds. For example, both increases and decreases in asymmetry scores have been reported for anxiety potentially due to the differential effects of subtypes (e.g. “worry” vs “panic”).

Frontal Asymmetry and Other Disorders

Frontal asymmetry also isn’t unique to depression. Changes in trait (resting) frontal asymmetry have been reported for schizophrenia, OCD, adults with ADHD, autism, panic disorder, whilst state frontal asymmetry changes have been reported for children with ADHD, bipolar disorder and PTSD. However, one large-scale study (n=2475) which compared 6 disorders only found significant resting-state asymmetries for patients with first episode schizophrenia and major depression (and in the opposite pattern to what might be predicted for depression- see figure) demonstrating the inconsistency in the literature.

From Gordon et al, 2010: Eyes Closed EEG Alpha Asymmetry across Clinical Disorders Using z scores to compare clinical groups with age appropriate healthy controls, the First Episode Schizophrenia group shows greater left lateralized EEG alpha asymmetry, while the Depression group shows a trend towards greater right lateralized alpha asymmetry. This was found for the Eyes Closed but not the Eyes Open condition. No other clinical groups showed significant effects for EEG alpha asymmetry

Summary

Despite the large number of studies analyzing frontal asymmetries, there is still an absence of consistent evidence to support its use as a biomarker for depression. Conflicting evidence and the finding that other disorders can also show asymmetries suggests that this broad EEG marker can’t readily be applied to heterogeneous disorders. Instead it’s utility arises by identifying the clinical groups, symptoms, or circumstances, where it is most relevant. But to do this, there has to be more consideration of the methodological confounds (see Human Brains and the Control Issue) that can adversely influence the results and a greater need for standardization across studies.