The symptoms of decline suggest not just changes in Mood & Outlook but a fundamental breakdown of the Social Self.

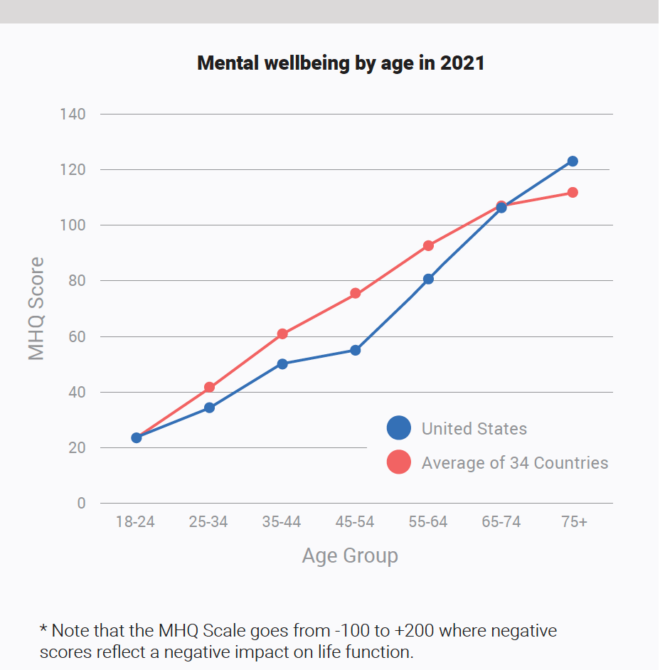

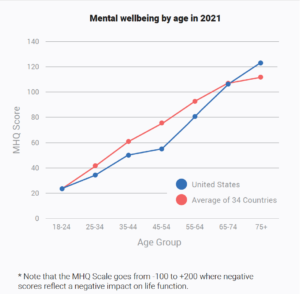

The Global Mind Project commenced in 2019 with a sample of a few thousand people across four major English-speaking countries (US, Canada, UK and India), growing to 223,000 across 34 countries in 2021. The 2021 data showed poorer mental health of each successively younger generation across the Internet-enabled in each of the 34 countries sampled, a trend that has been seen in the Global Mind data since 2019 prior to the pandemic.

The Decline of Mental Wellbeing in Young Adults

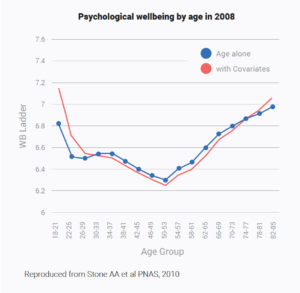

This pattern is contrary to patterns of psychological wellbeing observed prior to 2010. For example, in 2008 the younger age groups (18-24) showed the highest levels of mental well-being (Stone et al., 2010), albeit measured in those studies with a more limited set of questions largely pertaining to the MHQ dimension of Mood & Outlook. This argues strongly that the pattern by age is not a reflection of a generally increasing mental wellbeing as we age but rather a generational decline.

What specifically is declining in younger generations?

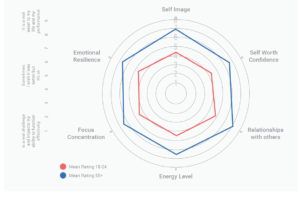

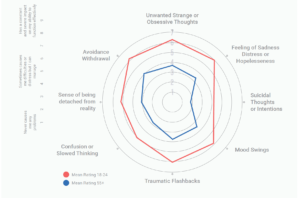

Several factors generally identified as positive assets in the older generations 55+ (>5 on the 9 point scale shown in the graph below) were rated as challenges (<5 on the 9 point scale) by the majority in the youngest group (18-24 years old). These included Self-image, Self-worth and confidence, Energy levels, Focus and Emotional resilience.

In addition, 7 problems that were rated as manageable or better in older adults 55+ (ratings <5 as shown in the graph below) were rated as challenges that were relatively unmanageable by the majority of those 18-24 (>5). These included in order of the most significant difference between older and younger adults: Obsessive and unwanted thoughts (largely around relationships), Feelings of sadness, distress or hopelessness, Mood swings and Detachment from reality. In addition, Suicidal thoughts and intentions, while not experienced by the majority of young adults like the other symptoms shown, was also among the most substantially increased in young adults.

Beyond Conventional Psychiatric Diagnoses: Challenges with the Social Self

What does this pattern of symptoms tell us about what is going on with younger generations? For one thing this profile of challenges (and at the extreme ‘symptoms’) that afflicts the majority of young people around the world does not fit neatly into any single conventional diagnosis. Rather it suggests something more, and different, from conventional diagnostic types.

While many of these young adults report anxiety and mood issues which are typically highlighted when discussing the mental health challenges of young people, they also express many concerns that directly affect social functioning or what we call “Social Self”. The Social Self metric in the Global Mind data is an aggregation of various elements that define how individuals operate in a social context. This includes concerns about self-confidence, a sense of doubt or even inferiority reflected by feelings of guilt and shame, difficulties in emotional control in social situations, challenges forming relationships with others, a sense of being detached from reality and other factors. As an aggregate metric it provides a way to assess a complex phenomenon of how we function within the social fabric. Viewed in this way, the Social Self is the dimension that has declined the most in younger generations, followed closely by Mood & Outlook. In contrast dimensions such as Cognition and Drive & Motivation have declined much less.

Numerous questions arise about these observed effects amongst young adults. What is responsible for this rapid decline? The fact that these effects occur across all countries suggest a commonality is largely responsible for the observed decline in Social Self.

Is the Internet to Blame?

The 34 countries where this decline is observed are diverse in the growth of their economies, and levels and changes in inequality. They are also diverse in their experience of political instability. However, one factor that is common amongst the populations studied in these 34 countries is that they are all internet-enabled, suggesting that increasing technology usage might be a factor in the observed trends. With smart phone use beginning to take off around 2010, the youngest cohort in this study are the first group to have grown up in an internet-enabled, tech-focused world.

With data showing average screen time ranging from seven to ten hours a day, this likely results in both diminished and distorted social interaction. With only few waking hours remaining, the Internet has taken over time previously spent in in-person social interaction. Furthermore, previous studies (e.g., Lin at al., 2016) have shown a correlation between extreme tech, especially social media use, and psychiatric difficulties and therapy for such conditions.

With virtual interaction lacking many of the dimensions of communications as in-person interaction there is also growing evidence that our neural systems designed for social interaction may not develop and function as well in the virtual medium (Dickerson et al., 2017) where the ability to process and understand important subtle cues like non-verbal behavior, eye-contact, and emotional expression are diminished.

Consistent with an Internet-based explanation, a report by Deloitte showed that 92% of 4000 Gen Z respondents were concerned about the “generational gap that technology that was creating in their professional and personal lives.” 37% “expressed concern that technology is weakening their ability to maintain strong interpersonal relationships and develop people skills”. In addition, other influences are also possible where fears for the future are amplified in younger generations, although further amplified by Internet-based media. For instance, A Pew Research report stated that “when asked about engaging with climate change content online, those in Gen Z are particularly likely to express anxiety about the future. Among social media users, nearly seven-in-ten Gen Zers (69%) say they felt anxious about the future the most recent time they saw content about addressing climate change.”

While more research is required to understand the impact of our technology-enabled social environment on our Social Self, the dramatic decline calls simultaneously for society to experiment with mechanisms to reverse it.

References

Deloitte Insights. Generation Z Enters the Workforce.

https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4055_FoW-GenZ-entry-level-work/4055_FoW-GenZ-entry-level-work.pdf

Dickerson, K., Gerhardstein, P., & Moser, A. (2017). The role of the human mirror neuron systemin supporting communication in a digital world. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 698. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00698

Lin, y. L. et al. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults.Depression and Anxiety, 33(4), 323–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22466

Newson, J.J. Sukhoi, O., Pastukh V., Taylor, J., Topalo O. and Thiagarajan T.C. Mental State of the World Report 2021. Global Mind Project. Sapien Labs.

Pew Report, May 2021. Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement With Issue.

Stone, A.A., Schwartz, J.E., Broderick, J.E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(22),9985-9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003744107