What are the fundamental principles of biological intelligence. Here is a theory that brings together various foundational theories into an integrated framework, one called practopoiesis or a theory of hierarchical adaptation that is ‘poietic’ in nature.

In the previous post I listed a set of ideas proposed by numerous scholars on various foundational theories underlying the nature of intelligence. By adopting the wisdom of all these concepts, I suggest one single set of fundamental principles by which biological systems get intelligent. In other words, a minimum and necessary set of conditions that need to be satisfied to create a living intelligent agent. I call this practopoiesis, a theory of hierarchical adaptations that is poietic (i.e. creational) in nature.

These conditions are:

1: Knowledgeable monitor-and-act machinery

An intelligent system must consist of numerous agents that monitor situations and act such as to change the situation. These agents act alone or in concert. We essentially decompose a living body into a collection of monitor-and-act units implemented in a form of molecules, cells, and collection of cells into organs. Each unit has knowledge about what to do. Examples of actions of monitor-and-act units are various, ranging from intra-cellular functions such as gene expression and channel opening on a cell membrane to functions executed in concert by entire organs such as those of the liver, kidneys, hearth, pancreas and, of course, the brain.

Each unit can also be described as a regulator or controller (from Control Theory), and this in turn makes the discipline of cybernetics applicable. Monitor-and-act units have the knowledge on when and how to act and this is essentially cybernetic knowledge, i.e. knowledge of how to control. The good regulator theorem tells us that the knowledge of monitor-and-act units forms a model of the environment (the Umwelt) in which the agent lives. And the variety theorem tells us that the more complex the environment, the more such units the organism will need. That is, the organism’s ability to survive is related to the amount of knowledge that it possesses. This then implies that, if an organism is to improve its intelligence, it needs to a) increase the number monitor-and-act units and b) supply these units with correct knowledge about the surrounding world.

Monitor-and-act units can be also viewed as mechanisms that adapt the organism to the environment. Thereby, practopoiesis is fundamentally also a theory of hierarchical adaptations.

2: Poiesis organized into a hierarchy

Not all monitor-and-act units are present at birth. An organism must create many of those units. By doing so, the organism sort of bootstraps through interaction with its environment. This “bootstrap” has been characterized by the theory of autopoiesis, from Greek αὐτo- (auto-), meaning ‘self’, and ποίησις (poiesis), meaning ‘creation, production’, essentially meaning self-creation. Practopoiesis states that an organism can be seen as autopoietic (self-creating) only when we view the organism as a whole. However, an organism may be autopoietic (self-creating) as a whole, but have components that do not create themselves. Rather, if we investigate how individual monitor-and-act units came about, we see that each such unit is being created by some other monitor-and-act unit (the proper term is allopoiesis —allo is a Greek prefix meaning ‘other’ or ‘different’). One monitor-and-act unit’s adaptive job is thus creation of another monitor-and-act unit, whose job then may even be to create a third monitor-and-act unit. For example, genes directly create proteins, and proteins can directly affect our reflexes. But reflexes cannot directly create proteins, and proteins cannot create genes. So the relationships are not symmetric but organized in a hierarchy. (For indirect interaction between those see the third condition, below.) Thereby, a creation chain within autopoietic systems can be near decomposed into a hierarchy that is driven by this rule:

If unit A creates unit B, then unit B cannot be involved in creating unit A.

In general, practopoiesis states that cybernetic knowledge at each level of the hierarchy needs be shielded from the level above. If the knowledge is not shielded, the intelligence of the organism as a whole would quickly degrade. This knowledge shielding requirement is a generalization of a role in biology specified for the relation between DNA and proteins known as the central dogma of molecular biology. Practopoiesis generalizes this central dogma to all levels of poiesis or creation, or a conceptual framework of an adaptive hierarchy of poiesis.

3: Embedded feedback for all units

So far, based on the two rules above, we have established that, to be biologically intelligent, we need a set of knowledge-laden monitor-and-act units and we need to organize them into an allopoietic (other creating) hierarchy. In this hierarchy, the monitor-and-act unit A that creates unit B cannot be acted on by, or receive information from B. So, where does A then gets its inputs from? In order to ‘monitor’, a unit needs observe something. Where are these observations coming from?

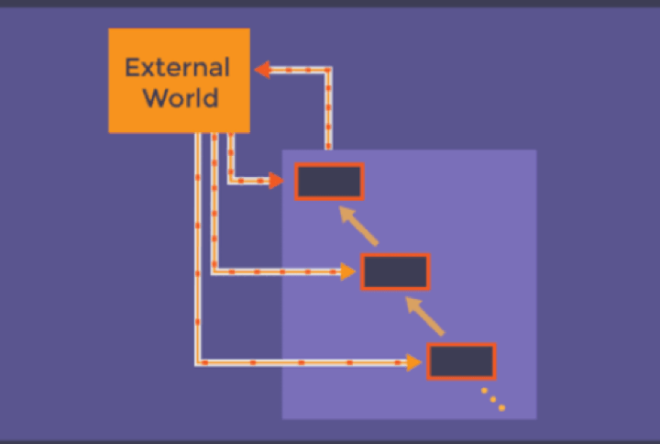

Practopoiesis theorizes that all units, irrespective of the location on the hierarchy, must receive input from the environment. Essentially, each unit at every level in the hierarchy has to close a loop with the outside world. They do not have to have a direct ‘wire’ to outside. It is ok if this information arrives indirectly. Nevertheless, whatever triggers a monitor-and-act unit to act must contains relevant and reliable information about the outside world. Without feedback from the environment, monitor-and-act units do not have a purpose. The more accurate the environmental information, the more the unit will be able to help the organism’s survival and well-being.

Thus, practopoiesis or the theory of poietic hierarchical adaptation suggests that to achieve intelligence (or survival in general), biology obeys three fundamental principles: (i) monitor-and-act units (ii) organized into a poietic hierarchy and (iii) each receiving accurate feedback from the environment.

Challenge : could You create or conceive an artificial intelligence system capable of solving Bongard problems faster then any biological human brain?

🙂

Hello,

An interesting thing about Bongard problems is, when you look at them from the perspective of machines, there are infinitely many correct answers to that problem. The reason we humans agree on a given answer as the only correct answer is that we share similar human basis on what the world should be like. In the language of machine learning we have similar inductive biases; in the language of Bayesian stats, we have similar priors; in the language of statistics, we have similar assumptions of the world.

So, to your question: Can we make an AI system capable of solving Bongard problems (coming up with the same solutions humans do), the answer is principally affirmative. However, we first have to make sure that the AI system has the same inductive biases as humans do. This is not an easy task. Take a look at the concept of AI-Kindergarten as a tool for providing machines with human-like inductive biases.