The DSM has defined psychiatry for 60 years. Yet its symptom based criteria for defining ‘disorders’ does no better than random when applied to comprehensive symptom profiles in empirical data.

Assessment of mental illness by western psychiatry utilizes the DSM or the Diagnostic or Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Compiled by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The DSM creates ‘diagnoses’ by essentially defining a criteria for grouping together a set of symptoms which are then termed ‘disorders’. These ‘disorders’ include Major Depressive Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, ADHD and Autism Spectrum Disorder among other. The grouping is based not on any underlying understanding of etiology or cause but rather by their perceived co-occurrence. These criteria have evolved over the years, and are concocted by a committee that subjectively draws from their patient experience. If enough of them find patients complaining of something or other that’s not part of the criteria but is alongside existing criteria, they might update the criteria to include that new complaint. What has evolved now is a method of dividing up of symptoms based on 2-3 anchor symptoms – symptoms you must have and 3-6 optional symptoms from a long list. These criteria are then declared to be ‘disorders’. The logic is that if they tend to turn up together, they must be part of the same or similar underlying causes. However there are some critical problems with this because fundamentally there is no understanding of underlying cause.

Symptoms map to many underlying causes

This method is very similar to saying if you have some kind of pain in your stomach (e.g. cramps, sharp pain) in addition to 4 out some list of 12 other symptoms such as fatigue, loss of taste, fever, cough, cold, etc. then you have ‘General Stomach Disorder’. As you can see quite easily there are numerous underlying causes for stomach pain from bacterial infections to tumors to intestinal obstructions and more and many other causes for those optional symptoms. Therefore, if we consider a disorder or diagnosis to be indicative of a unified cause then General Stomach Disorder is neither a diagnosis nor a disorder. It is simply a name for a loose grouping of symptoms.

But do these groupings separate people by symptom profiles?

Given that these groupings don’t represent a real disorder or diagnosis, the next most useful thing is that these criteria at least group people by classes of symptoms, where people within a group are more similar to one another in their symptom profiles and therefore at least more likely to have a similar type of underlying cause. For example, generally if you have some combination of a fever, sore throat, chills, headache, muscle fatigue, cough and cold you are likely to have an infection rather than some other kind of problem. Of course the diagnosis could be any of a hundred kinds of bacterial, viral or other infections but at least from the symptom profile you can infer with some certainty that it is an infection of some kind. For such inference to work, these disorder groups (or groups constructed using DSM symptom criteria) should each be reasonably separable from each other. We put this to the test but found fundamental issues – and the short answer is that they are no better than random but read on.

DSM Criteria are very heterogeneous

Since the DSM criteria include 2-3 required symptoms and a combination of optional symptoms numerous symptom combinations produce the same diagnosis or ‘disorder’ assignment. For example there are 277 possible combinations of symptoms that can get you assigned to PTSD (we shudder to say diagnosed). Now when you compare the symptom profiles of individuals all assigned to the same ‘disorder’ i.e. within a disorder label, is it at least more homogeneous than between two disorder groups? Not really. The symptom profiles of people with PTSD can be as different from those of others ‘diagnosed’ with PTSD as compared to a person ‘diagnosed’ with ASD. So where does that leave you?

Figure 1: From [1] Symptom profiles of two people diagnosed with depression shows how different two people with the same ‘disorder’ can be.

DSM Criteria do not consider the full breadth of symptoms

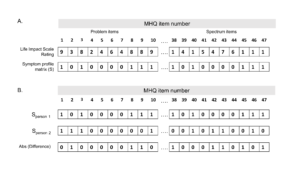

We mentioned above that the DSM criteria typically involves 5-6 symptoms including those that are mandatory and those that are from a list of options. However none of these lists of options span the entire spectrum of symptoms and many of the symptoms overlap across ‘disorders’. Thus DSM criteria also exclude a whole lot of symptoms in how they consider these groupings. For instance while you have to have 3 or 5 from a list of 10 symptoms there is no rule saying that you can’t have symptoms outside that list. This is important because there is a large universe of symptoms – 47 in our list. So what does this mean for the 20 or 30 symptoms not considered in defining the ‘disorder’? The consequence is that it many people are assigned to multiple disorders. In fact multiple ‘disorder diagnoses’ are the norm with 60% of people with 5 or more mental health symptoms ending up with anywhere from 2 to 10 ‘disorders’. On the other side, a big chunk of people don’t match any of the criteria exactly and even if they have 10 really bad symptoms, don’t meet any DSM-based ‘disorder’ label.

Figure 2: From [1] Symptoms associated with ‘disorders’ according to the DSM

And finally, when put to the test it does no better than random

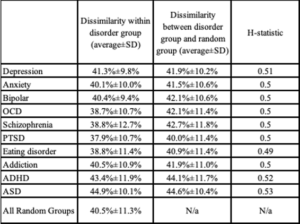

So now with all this, what happens when you capture the entire symptom profile of a lot of people (we used 100,000 people from the Global Mind dataset) and map each individual to the DSM disorder criteria for 10 major disorders? Are people who ‘have’ ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’ at least kind of separate from people who ‘have’ ‘ADHD’ or ‘Depression’? To figure this out we compared the entire symptom profiles of each pair of individuals to look at their symptom distance or ‘dissimilarity’. The symptom dissimilarity or distance was computed as the sum of the difference between all symptoms (where present was coded 1 and absent 0) divided by the total number of symptoms as shown below.

Figure 3: From [1] Computing symptom dissimilarity or symptom distance between pairs of individuals

We then created random groups of people and looked to see if the people within each ‘disorder group’ could be separated from this random group by calculating the Hopkin’s Statistics. This statistic looks at whether an individual is closer in symptoms to more people from his/her disorder group than those from the random group as follows.

Table 1: From [1] Symptom distance (i.e. dissimilarity) within and bewteen disorders and corresponding Hopkins Statistic.

A value of 0.5 means that any individual is no closer to his/her own disorder group than to a random group. Higher values mean that they are closer and closer to their own group than the random group. A value of 1 means they are totally separate. This means that the higher this number is the more this data would empirically separate into these groups using machine learning methods such as clustering. However for every single DSM based ‘disorder’ the Hopkins Statistics was between 0.5 and 0.53 – no different from random.

How can this have happened?

How is it possible that an entire field has been based on something totally random and the world bought into it? No matter that treatments never worked well or any of the other fallouts of such a system. How did that happen? We’re scratching our heads but our best guess is that it’s a combination of these reasons:

First, the symptoms and distress they cause are real and people are desperate to hold on to something – anything. Just having any label, no matter how meaningless, provides comfort and in many cases to abdicate responsibility for its consequences. ‘I do it because of my ADHD” is a lot better than just saying “I have a challenge with these kinds of things”.

Second, back in the early 1950s when the DSM first came into existence, computing and big data weren’t a thing. Machine learning wasn’t a thing. So you couldn’t really collect data from a lot of people and analyze it. Instead you relied a lot more on intuition. And the intuition of these experts was the best thing we had. From psychiatrists to journalists, why would you question the wise old men who cooked this up? And now? Now they are in too deep. The American Psychiatric Association has a lot invested in this framework and spends a lot on PR to push this agenda. Its lucrative and not in their interest to rock the boat. Besides, there is yet no alternative.

Where do we go from here?

The first thing is probably to figure out how people best separate by symptom profiles. At least this will help group people by real criteria which will be one step in the direction of figuring out what is causing them.

References

[1] Newson, Pastukh and Thiagarajan Poor Separation of Symptom Profiles by DSM Disorder Criteria, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2021 Nov 29;12:775762.

Here’s one answer to “where do we go from here”: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666144620300198

From personal experience, I have long suspected the gist of this article to be true.

The crucial issue now is to eradicate immediately this tragic “statistical” anomaly and to learn lessons to inform, redesign and enhance subsequent diagnostic tools in order to achieve more positive outcomes in the future. A brighter future should be written today; however, these past practices will, undoubtedly, remain present for the foreseeable future.