Where is language in the brain? Its not as clear as once thought.

A computer engineer needs language skills. Though they speak in various codes to their machines, they speak in English to their clients. Brain surgery in Broca’s area – a part of the brain affiliated with language – would surely be career death. Or so Patient FV was told when doctors found a tumor in the center, and he agreed to its surgical removal.

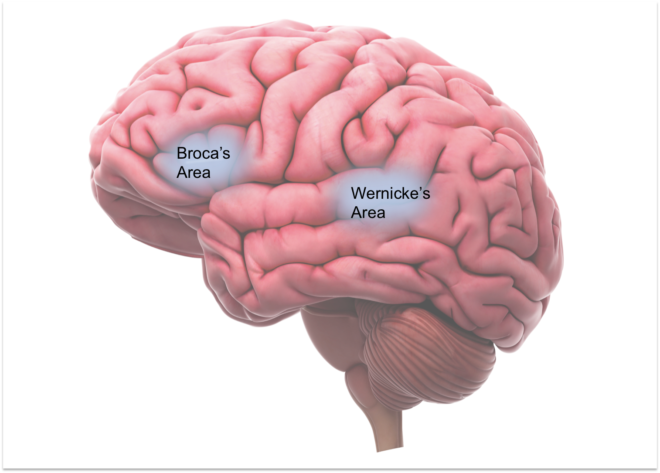

Dr. Paul Broca identified the posterior inferior frontal gyrus as an area essential for language skills following the biopsy of a peculiar patient in 1861. Patient Tan, as he came to be called, could only say one word. To any question his answer would invariably be: “tan tan”. Aside from this, his intellectual capacity seemed largely intact.

When his biopsy revealed a large lesion on the posterior inferior frontal gyrus, Broca thought he might be onto something. When a lesion in the exact same area of the brain was revealed in a second patient with linguistic difficulties, Broca knew he had discovered something fascinating. Broca’s area, as it came to be called, has been identified as a linguistic hub ever since.

Patient FV’s surgery was a success, and his post-surgery recovery began as expected. His language skills had been seriously impacted, but the deficits didn’t last. When patient FV returned to work, both his computers and his clients could understand him just fine. How is this possible?

The secret is brain plasticity. Broca himself recognized that some patients with head trauma would initially lose their language skills, but might regain their abilities with practice over time. He postulated that perhaps the other side of the brain was able to compensate for the damage done. He was right. Scientists believe that Patient FV’s brain healed itself. The tumor had been slowly growing in the Broca area of his brain for some time. This slow progression, they believe, gave his brain time to adapt. (see related article A Changing Brain is a Normal Brain)

Not only can our brains adapt when faced with trauma, they are adapting even under normal circumstances. The result is that no two brains is exactly alike. This applies to all areas of the brain, even the parts that deal in language.

Though Broca’s area has been identified as an important area for linguistics, there is ample room for variety. Most right-handed people speak using the left side of their brain, but left-handed people fall into a much more complicated distribution. 68 percent use the right side, 19 percent use the left and the remainder use both. Not only is there no one language center, our ability to produce language can be directed from completely different sides of the brain.

Ten years after the discovery of Broca’s area, an unusual patient made Dr. Carl Wernicke question whether there might be another important linguistic area in the brain. His patient could speak just fine – various grouping of words flowed effortlessly from between his lips. The words he strung together, however, made no sense. The patient didn’t seem to realize he was talking gibberish.

When the patient’s brain was autopsied, Wernicke found a legion in the posterior temporal lobe. This area, he reasoned, must be affiliated with understanding and processing language, while Broca’s area is responsible for the physical production of language. In other words, a lesion in Broca’s area interfered with the motor skills necessary to make linguistic sounds, while a lesion in Wernicke’s area interfered with the ability to understand and properly use language.

Much like the variance in Broca’s area, Wernicke’s findings have proven more fluid than fact. One patient might have a tumor removed from Wernicke’s area and be perfectly fine, while another will never speak coherently again (see also The Curious Outcomes of Neurosurgery).

No one wants to be diagnosed with a brain tumor, but finding one in either Broca’s area or Wernicke’s area is particularly terrifying. Surgery may save your life, but destroy your ability to communicate. Most of us would rather lose a limb.

Thankfully, modern technology is beginning to mitigate this terrifying possibility. We have long known that every brain is put together differently, but now we can see how each individual brain works. Surgeons can map the brain using imaging technology (also read 7 ways to peer into the living human brain) and avoid the centers that their patient needs for both language production and comprehension. The technology isn’t perfected yet, but it is only getting better. It’s a brave new world in neuroscience.

Erin Wildermuth is an aspiring MD/PhD student and is presently working in a neuroscience lab studying memory.

Is this a joke?!? How can you be so MIS-informative!!! In 95% of the population, language is localised to the LEFT hemisphere. This figure WRONGLY shows Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas on the right hemisphere. Please correct this.

Thank you so much for noticing and pointing out that the image was flipped! It has been corrected.