Self-report survey has been one of the main tools in the study of human populations in matters of mind across numerous disciplines from Sociology to Psychology to Political Science. After all, only each individual knows the perceptions, feelings or thoughts of their mind. The Global Mind Project uses a relatively new methodology of data acquisition: Internet based outreach, directing people to an anonymous self-report assessment that they take for the purpose of getting their own score and personalized self-help report. Here we will unpack each part of this methodology towards answering the question of whether the Global Mind Project data is representative and show a comparison of responses of marital status in the United States data from the Global Mind Project to data from the United States Census (spoiler: they track quite well).

What is representative?

One of the main goals of survey design has been to get a representative sample of a population, meaning that the results of the survey sample would reflect the outcomes you would get for the whole population. Typically surveys that claim to be representative will recruit participants stratified by age, gender, and income groups. Yet there are numerous other factors that can influence the representativeness depending on what you are asking about. For example, how you feel or think about something could depend on the type of occupation you are in. Truckers and teachers have around the same income on average. I imagine they think quite differently about a lot of things. And if you are asking about mental health, they probably have a whole different set of problems. How do you ensure that you proportionally represent occupations in your sample, let alone just truckers and teachers? There are so many other factors as well that can influence your answers, from religious affiliation to family structure to lifestyle habits.

Many global polls and surveys have as few as 1000 participants per country. For large countries like India for instance, where the population is over a billion and the diversity is huge, it is laughable to claim representativeness with that sample size – although they do.

Bottom line – moving towards representativeness requires a lot more than age/gender/income stratification. No survey captures and represents all demographic segments – not just because of the scale but also because many of these factors are unknown and you can’t stratify easily by multiple factors that you don’t even know until you ask the person.

So how do you get to be representative?

The bigger the better

The best way to move towards being representative is scale – larger scale will get better and better at approximating the overall population. Traditional methods of survey which involve phone calls or in person visits are expensive and time consuming and limit the number of people you can survey. The Internet enables much larger scale by changing the cost equation dramatically and also enabling a speed that is simply not possible with a surveyor in the middle. For example, the Global Mind Project sampled has sampled ~1 million since its launch mid-2020 and ~500,000 people in 2022 alone (a number that is growing annually), while other well-known global studies sample a maximum of 150,000 per year with typically 1,000 – 2,000 per country.

Of course it is not possible to reach low-literate or offline populations this way. However the Global Mind Project is focused on the Internet-enabled world. You can target by specific age, gender groups and geographies through outreach on various Internet platforms. The Global Mind Project uses primarily Google and Facebook.

But how do you know you aren’t getting people from just one group or just one type of person? Well, you don’t – unless you ask.

More demographic information

Given that there are so many different influencing demographic factors – particularly of one’s mental state, which is the core of the Global Mind Project, we can’t know a priori what those are and who is part of which group. It is therefore not possible to recruit only those people who are important for representativeness. The solution is to ask. Thus rather than trying to preselect respondents, within each age-gender-geographic group, we let anyone take it and ask a lot of demographic factors from income to ethnicity, education, employment, the type of environment they live in, family or household structure, and more. This makes it possible to provide various segmented views of the population. And as the data gets larger it then becomes possible to create more demographically representative weighted averages of the population.

But how do you ensure that people aren’t faking their responses?

Removing the middleman and making it worthwhile

Traditional survey requires the participant to tell their answers to a real person, and in many cases, identify themselves. This poses a challenge when you are asking sensitive questions or questions about very private things like we do in the Global Mind Project. Most people don’t want to admit problems of certain kinds to another person and will often moderate their response to appear a certain way to that person to avoid embarrassment or judgement. By making it anonymous we take away this fear. The surveyor may also have their own biases or attitudes that seep in and influence how the respondent answers. This is also eliminated.

Secondly, people are not paid to take the Global Mind MHQ assessment. Nor do they take this survey simply because they have a lot of time on their hands to participate in research. Both of these factors can create distorted motivations for how people answer. Instead, people take this survey in order to get their mental wellbeing scores and individualized self-help report. This adds a very different type of motivation – to get an accurate picture of themselves they have to answer honestly and stick with it through the 15-20 minutes it takes to complete it.

Various internal checks that we have embedded within the assessment enable us to determine which records are legitimate and which are not.

So now, how representative is the data?

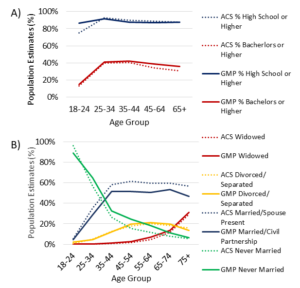

Well we can do some checks, especially for countries where Internet penetration is high such that the Internet-enabled population is almost the whole population. For example, in the United States, various global trends captured by the US Census Bureau, for example in the American Community Survey, which is the largest survey out there are mirrored in the Global Mind data. The graphs below for example show that trends of marital status and education by age are very similar. You can find a more detailed comparison of the Global Mind Data to US Census Bureau data as well as other national datasets here.

Figure 1.

Of course it is important to keep in mind that the Global Mind Project only samples the Internet-enabled population. Consequently the lower the Internet penetration, the more the sample will deviate from national representativeness. Rather it provides a comparison of people of more similar access and means around the globe.

How we construct country aggregates

Generally, in the country aggregates we show in our reports, we use an age-gender weighted average, where weightings are based on the representation of the age-gender group in the population. For countries with higher Internet penetration this will be closely representative. Whereas in countries where the Internet penetration is low, the Global Mind data tends to represent a more educated and higher income demographic than the whole country, but be pretty representative of the Internet enabled population of the language group surveyed.

The data is open for researchers around the world for non-commercial purpose so feel free to explore it and convince yourself. You can get access through our researcher hub.