Physiological inquiry using EEG could ultimately put the learning styles debate to rest and even shed new insights

Every Monday morning children aged from teeny tots to near-adults line up outside of classroom doors, ready to learn. The expectation in many countries is that their teachers have spent considerable time preparing concepts and teaching strategies that incorporate different learning styles. In 2009, 82 percent of teacher trainees interviewed in England agreed that “individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style.” A 2014 study conducted across five countries places the number of teachers who are also learning style enthusiasts closer to 95 percent.

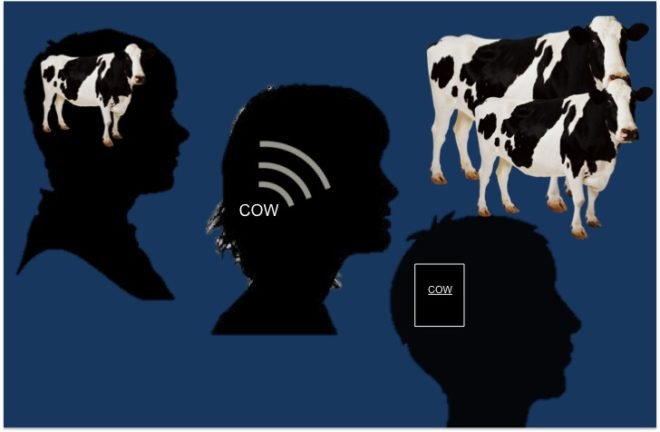

The VARK model

Yet teachers are relatively new to this whole concept. Psychologists were thinking about different types of intelligence, personalities, and learning styles long before the front-liners of education took note (see related post on Linking Cognitive Science with Neuroscience). The concepts that would eventually make up the VAK model, for example, were originally developed in the 1920s.

By the 1970s, the idea of teaching to accommodate for various learning styles was becoming increasingly popular. VAK, formally introduced as a complete model in the late 1970s, became the most widespread model. According to VAK, the most common learning styles include visual, audio, and kinematic modalities. In the late 1980s, Neil Fleming revised this model to include an additional reading/writing component. The new and improved system is called VARK and remains popular today.

Criticisms of Learning Styles

Though learning style paradigms have played a role in curriculum design, educational implementation, and program evaluation, they are not without controversy. Critics point to a lack of robust evidence for the existence of distinct learning styles, arguing that resources spent in support of an unproven system would be better spent elsewhere. Studies in support of distinct and relevant learning styles have been attacked on several grounds, including small sample sizes and mistaking correlation for causation. Critics also point to a number of studies that do not support learning style theories at all.

At most, these critics argue, learners have preferences regarding how their information is packaged. These preferences do not translate to significant deficits in their ability to learn different ways. A preference is not the same as a distinct style. Some even argue that catering to perceived learning styles may do students a disservice – unintentionally encouraging them to under develop their weaker powers of understanding.

Just as popular media was once quick to publish learning styles as fact, they are now quick to publish critiques of these theories as fact. “Neuromyth” has become a frequently used media buzzword, effectively telling readers that believing in learning style modalities is akin to believing that humans only use ten percent of their brains or that not drinking enough water will result in brain shrinkage.

Inconclusive results

Contrary to what the media would have us believe, the only fact is that our evidence, one way or the other, is inconclusive. While this may be a good reason to hit the brakes on teacher training programs that emphasize learning styles, it would be premature to announce the concepts discredited.

Part of the problem is that learning style studies have embraced study designs prone to compounding factors and personal interpretation. Studies that group learners according to modality concepts and then extrapolate the validity of models based on learning objectives can be useful, but they are far from the holy grail of social science research.

Using EEG for a physiological view

Luckily, some researchers are turning to a more physiological approach. A 2016 study, for example, by Chailerd Pichitpornchai and PhD student Sarawin Thepsatitporn at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand used EEG to compare subjects’ VARK-determined learning style to their visual event-related potential (vERP) readings. The results indicated that visual learners “exhibited larger P200 amplitudes at the occipital  site elicited by pictures” than reading/writing learners. The P200 is a positive deflection in the brain wave 200 milliseconds after presentation of the stimulus – in this case the word or picture. The occipital lobe is associated with visual processing and a difference in the P200 in this region could signify that there was a physiological difference between how these two groups of students processed the pictures they were shown. Though only a single study, these results indicate how useful a physiological line in inquiry may be to the learning style debate.

site elicited by pictures” than reading/writing learners. The P200 is a positive deflection in the brain wave 200 milliseconds after presentation of the stimulus – in this case the word or picture. The occipital lobe is associated with visual processing and a difference in the P200 in this region could signify that there was a physiological difference between how these two groups of students processed the pictures they were shown. Though only a single study, these results indicate how useful a physiological line in inquiry may be to the learning style debate.

In the end, putting the debate to rest may come not from the fields of education or psychology but from neuroscience.

No amount of EEG evidence can substitute for rigorously designed learning experiments to determine whether in fact the learning style construct is valid and a substantial enough factor in learning outcomes to justify expending educational resources on it.

Whether some students pick up information more efficiently in one manner than another seems to be beside the point. I thought the more connections, methods of presentation, senses used the better for all learners. More variety in input would equal more connections within the brain????