The sheer volume of scientific articles makes validation and discovery of results near impossible. The solution may lie in doing away with the journal article format altogether.

The scientif ic journal has its origins in 1665 with the publication of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in English and the Journal des Savants in French. These were journals of scientific observation meant to capture the emerging ideas of the natural and physical world. In the 1600s a handful of journals sufficed to communicate much of the emerging scientific thinking. As scientific endeavor expanded in the 1800s more journals came into existence. Many have come and gone but among the oldest, other than Phil Trans, which is the original scientific journal, are Nature which was founded in 1869 and Science which was founded in 1880.

ic journal has its origins in 1665 with the publication of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in English and the Journal des Savants in French. These were journals of scientific observation meant to capture the emerging ideas of the natural and physical world. In the 1600s a handful of journals sufficed to communicate much of the emerging scientific thinking. As scientific endeavor expanded in the 1800s more journals came into existence. Many have come and gone but among the oldest, other than Phil Trans, which is the original scientific journal, are Nature which was founded in 1869 and Science which was founded in 1880.

The growing volume of literature

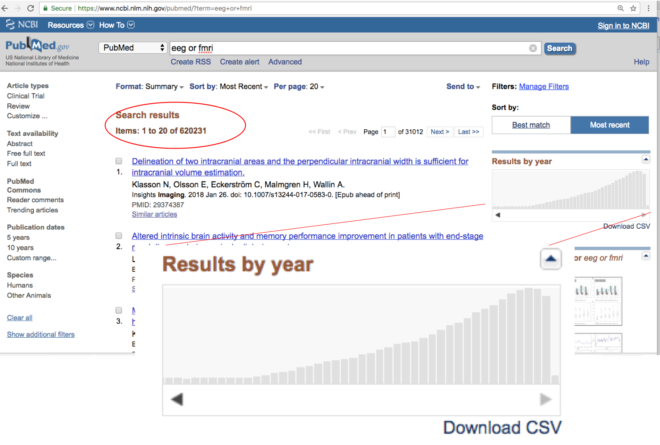

As scientific enterprise has grown so too has the number of journals and journal articles. Today we are faced with the enormous challenge of the sheer volume of the scientific literature. Human neuroscience, for instance, is a relatively new field that did not exist at the time Nature and Science established their journals. As a field largely ignored by these journals it has given rise to a new set of journals more specialized in this area. Today, even though human neuroscience is a relatively young field compared to the molecular and cellular studies favored by the ‘old’ journals, there are already over 500,000 published papers and the numbers just grow faster each year. As I wrote over a year ago, it is no longer humanly possible to ‘keep up’ with the literature. Even if you were to read a paper or two a day (which would be a lot if you were also to do your own work) this would amount to less than 0.1% of the total literature and about 1.5% of the literature published that year (based on 2017 human neuroscience numbers). This has implications of many kinds.

Compromised judgement and peer review

First, all these papers have to be reviewed by someone, and since no one knows the whole literature, it is impossible to truly judge a study in the context of the literature. Who can really know for sure which results are new and which are not? No one. More significantly though, since the task of peer review is already so time consuming given the volume of papers, who has the time to get into the methods and data in detail? The volume of papers and the voluntary nature of the peer review process is one reason the the peer review system does not bother with things like looking at the actual data or code – not even in journals like Nature and Science considered the top of the journal heap. This, even though everyone knows that the devil is often in the details – things like the quality of data and the parameter choices in algorithms. Indeed, in this mechanism of publishing, papers with made up data and buggy code, but with well written logically constructed stories can do better, and are even unwittingly preferred to the often messy and less easily interpreted results of biology. This is bad for science.

The challenge of finding specific results

Second, there is the problem of discovery of results. Finding journal articles has become easier today with online key word searches relative to past methods of rummaging through library catalogs and searching dusty stacks of journals in library basements. However, it is still not good enough and is tremendously compromised by the structure of journal articles. A journal article must have a particular length and ‘good’ articles tell a story. Often this will mean that an article does not just contain one result but many results. Furthermore, a collection of results must be woven into a linear story even though it may have many directions. Nonetheless authors have to choose only one main point to communicate in the title, and provide key words relevant to this main point. Figure 6, panel C which may not speak to the main point, but contain something exceptionally important in another context, will never be found in any search and most likely submerge into oblivion.

Lost results and wasted public funding

Finally, if no one can know the literature, and its validity, then how exactly does all this knowledge benefit mankind? Not unlike consumer products, what reaches the public (and scientific community) is now based more on marketing than scientific merit. It has to do with which Universities and journals have more active PR efforts and who knows and can endorse the work being marketed, which in turn has to do with who the authors know and which meetings they attend and the visibility they can drum up, which in turn has to do with funding available for this peripheral activity. Consequently some 1% of the papers get all the attention and 99% slip into oblivion, unread and forgotten. That’s a lot of wasted public funding and human effort. Moreover, in most endorsements (or conversely critiques), since neither the reviewers, the editors or the endorsers have actually looked at the data quality or made sure there is no error in the code or got into the nuances of parameters chosen in the analysis, they are most often coming forth with heuristic judgements at best, which then perpetuate.

Moving towards a solution

So what is the solution? While some journals such as eLife and PLOS require data to be made available and have begun to talk about replicability, none solve the problems of discovery and validation of scientific results. In my view, the journal article is no longer the right format for scientific publishing. It is too complicated, forces linearity where it is not always appropriate, makes the discovery of individual results difficult, and makes the association of multiple datasets to one paper a hairy process for anyone to process (as we have found out as we aggregate public datasets into Brainbase). Rather the format of the scientific publishing has to move away from the journal article and more towards archives of structured, searchable individual results linked with associated data and code, and ultimately linked with one another so that webs of linked results can be explored.